I’ve been familiar with the work of exiled superstar artist/activist Ai Weiwei for some time, but have taken a particular interest in it over the last few years because of the way my own research has intersected with some of the preoccupations that run through his work. He has produced a large series of works around the bicycle, using this ubiquitous and unremarkable object as a frame through which to explore a range of topics including the alienating experience of consumer society and political repression in contemporary China. Alongside this, he has produced a growing series of works about refugeeism in various media, including ceramics and sculpture, prints, photography and video.

I’ve written about Ai’s bicycle work before, and, with Katarzyna Marciniak, about Ai’s vast documentary, Human Flow(2017), and my interest in these two strands of his work is in the way they are connected by a politicised concern with inequalities of mobility. It is unsurprising that an exiled artist should be fascinated by this theme, and the autobiographical, exhibitionistic focus of much of his art encourages us to read the work as personal expression.

Visiting Vienna this summer, I was lucky enough to see a comprehensive retrospective of his work at the Albertina museum entitled ‘In Search of Humanity’, and this career overview reinforced the thematic interconnections of his work. One room displayed some familiar bicycle pieces, including ‘Double Bicycle’ (2003) and one of Ai’s large-scale structures constructed from ‘Forever’ brand bicycles. Alongside these were two rather darker pieces I hadn’t seen before: ‘Rem(a)inders’ (2008), a large pile of tiny fragments of shredded bikes, and ‘Untitled (ICA)’ (2011), a smashed, flattened bicycle that looks like it was retrieved from the scene of a road accident and laid out on a mortuary slab.

- ‘Double Bicycle’, ‘Forever’, ‘Rem(a)inders’ and ‘Untitled (ICA)’ on display in Vienna.

This sense of quiet horror carried over into Ai’s refugee-themed work installed in adjoining rooms. This included a ceramic tower that resembles traditional Chinese porcelain but shows scenes from the journeys undertaken by 21st century refugees, an exquisite, hyper-real marble sculpture of the inner tubes used by people attempting sea crossings, and a large crystal ball sitting mysteriously on a bed of life jackets.

- sculptures by Ai Weiwei on display in Vienna

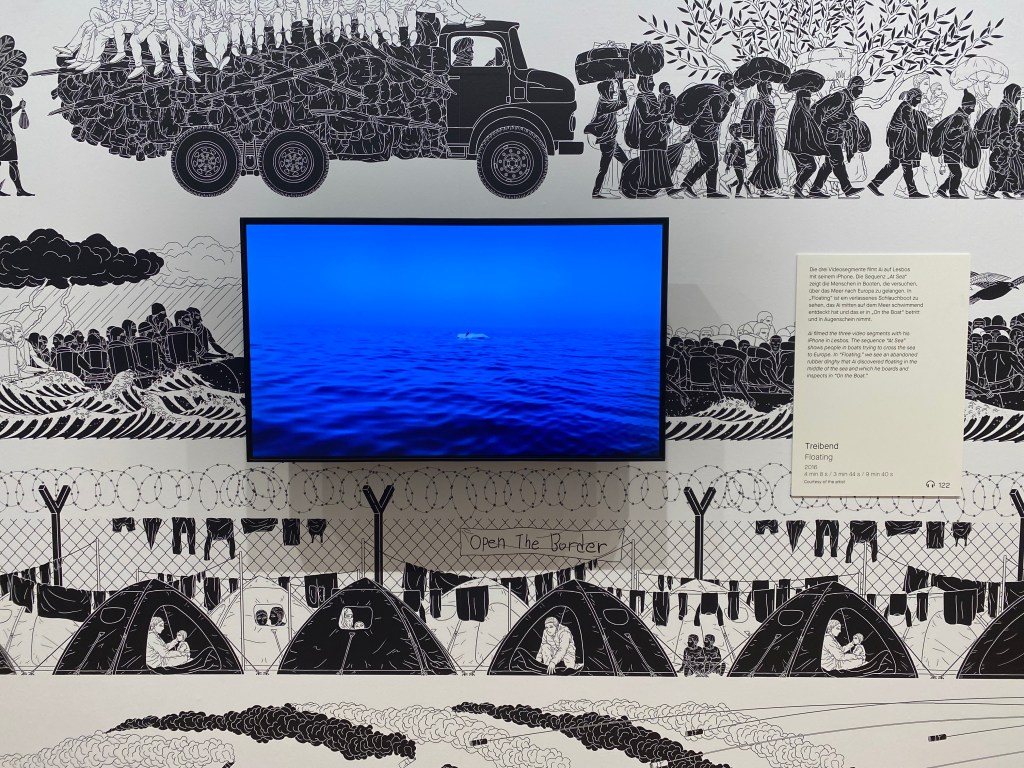

Displayed on an LCD screen, ‘Floating‘ (2016) showed short videos shot by Ai on his iphone in Greece on the shores of the Mediterranean, and on the wallpaper behind it, ‘Odyssey’ (2017) depicted the refugee crisis in scenes that invoke the imagery of Greek vases and graphic novels.

- ‘Floating’ in Vienna.

In the corner of one room stood a chipboard table with dozens of power points, a mobile phone charging station retrieved from an abandoned refugee camp, an object that testifies to the crucial importance of the mobile phone to the contemporary refugee.

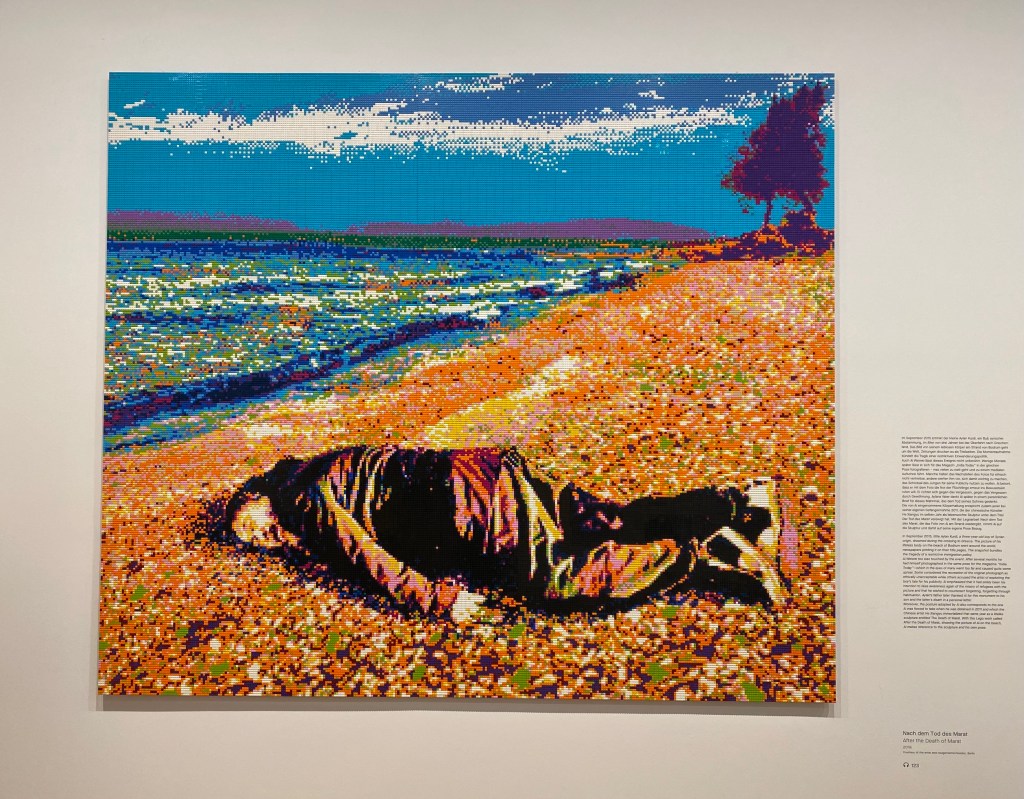

Alongside this work, which demonstrates the formal flexibility of Ai’s practice, were a number of large, spectacularly colourful images made from Lego. This is an interesting idea, a democratic form of image production that removes all traces of the hand of the artist from the work (although of course, it’s always unclear with Ai’s work how much of the creativity originates with Ai, and how much with the anonymous armies of apprentices and craftspeople he employs). There is also something jarring in the contrast between the blankly inexpressive, pixelated images and the traumatic experiences they refer to.

- ‘Nymphéas’ in Vienna

‘Nymphéas’ (2019), for example, named after Monet’s late paintings of water lilies, offers an approximation of an impressionist painting, but appears to show a drowned body on the seabed. Another, which looks like an early computer’s attempt to reproduce a Cy Twombly painting, shows a black line scribbled energetically on a blue background. The title explains that this is an aerial view that shows ‘The Navigation Route of the Sea-Watch 3 Migrant Rescue Vessel, June 2019’, an image that offers a counter-perspective to the subaquatic point-of-view of ‘Nymphéas’.

- ‘The Navigation Route of the Sea-Watch 3 Migrant Rescue Vessel, June 2019’ in Vienna

In some ways, the most confrontational of this sequence of Lego images is ‘After the Death of Marat’ (2018). This reproduces the notorious photograph of Ai lying on a beach in a restaging of the widely circulated press photograph of the body of two-year old Alan Kurdi, which was washed up on a Turkish beach after he drowned along with his mother and brother as the boat in which they were attempting to reach Greece capsized.

- ‘After the Death of Marat’ in Vienna

The title refers to ‘The Death of Marat’ (2011), a super-realist sculpture of Ai in the same pose, which, of course, takes its title from Jacques-Louis David’s epic imagining of the dead revolutionary. The recursive title implies that this piece, like much of Ai’s work, is in conversation with art history, but it also indicates that this is an image not of a tragic but inevitable event, but (as was the case with the assassinated Marat) of murder. What makes this more troubling still is the fact that this is rendered with the children’s toy that Aylan might have played with had he survived.

The sheer scope of Ai’s work in this retrospective reveals an artist who is restlessly trying to find modes of representation that are adequate to the shifting political landscape we occupy and the cycles of violence and trauma that shape it. The search for humanity, noted in the exhibition title, is Ai’s search for an ethical and engaging frame through which to view it.