- French poster for Peter von Kant (2022)

Introduction to a screening of Peter von Kant at the Dukes cinema, Lancaster, 8th Feb, 2023.

Peter von Kant is an adaptation of the 1972 film, The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, one of the most well-known works of Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Fassbinder was one of a group of young film-makers who began making films in West Germany in the early 1960s and came to be regarded as the exponents of what was called the New German Cinema. Rejecting the anodyne commercial films that dominated German screens, they understood cinema as a political tool and made films that explored the ways in which contemporary West Germany was shaped by its recent history and, in particular, the ways in which the legacy of fascism persisted.

Unlike some of the other directors associated with the New German Cinema, such as Werner Herzog or Volker Schlöndorff, Fassbinder was particularly interested in classic Hollywood cinema. ‘The ideal,’ he said, ‘is to make films as beautiful as America’s but which at the same time shift the content to other areas’. Rather than functioning as escapism, Fassbinder felt that the glamorous visual style and the emotional dynamism of Hollywood cinema could be used to confront audiences with urgent political questions.

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant was based on one of Fassbinder’s plays and is about the relationship between a successful fashion designer, her silent assistant Marlene, whom she treats abusively as a slave, and a young model Karin, whom she adores, but who has a husband and male lovers. As with other films by Fassbinder, these relationships are the arena for power struggles between lovers, and the way in which they view one another is always shaped by the wider social context in which they live. Tragically, their expectations of one another are incompatible so that, as Petra says, ‘I think people are made to need each other. But they haven’t learned to live together.’ Even though she knows Karin is unfaithful, Petra tells Karin to ‘Lie to me’, so that she can hold onto the fantasy that they are equally in love for a little while longer.

Even though the entire film takes place in one small room, Petra’s bedroom, nevertheless it is a film about politics, since their relationships are irretrievably determined by the class inequalities of contemporary society. Whereas in classic Hollywood cinema falling in love allows the protagonist to step out of their lives into a marvellous utopian neverland in which their lives are finally complete, in Fassbinder’s films falling in love only offers, at best, a temporary reprieve from the struggles of everyday life, mixed with bitter tears. In Fassbinder’s films, to borrow the slogan of late 1960s second-wave feminists, the personal is always political.

Fassbinder was very publicly bisexual and this film has come to be regarded as a key film in the history of queer cinema. It explores more explicitly than many of his other films, the dynamics of the relationships of women who live outside the conventions of heteronormativity. It also belongs to the tradition of the woman’s film and the classic Hollywood melodrama with which Fassbinder was fascinated, a genre of film that is preoccupied with the frustrations and struggles of women’s lives in the face of the constrictions and demands placed on them by marriage, motherhood and the impossible ideals of femininity.

As a film about a creator, The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant is also often understood to be a self-reflexive film about film-making in which the character of Petra – precocious, controlling and sadistic, self-important and cynical, jealous, addictive and self-pitying – is a self-portrait of Fassbinder.

With Peter von Kant, French director François Ozon, underlines this interpretation by making the protagonist a film-maker, rather than a fashion designer. Following the lead of several recent Hollywood remakes and adaptations, Ozon has swapped the gender of the central trio of characters, who are all now male. Peter is played by French actor Denis Ménochet, who looks very like Fassbinder, while the character of Peter’s young lover, Amir ben Salem, is named after Fassbinder’s Moroccan lover, El Hedi ben Salem, who starred in Fear Eats the Soul (1974), his bleak melodrama about racism in 1970s Germany. Consequently, Peter von Kant is almost a companion piece to the 2020 biopic about Fassbinder, Enfant Terrible (Roehler).

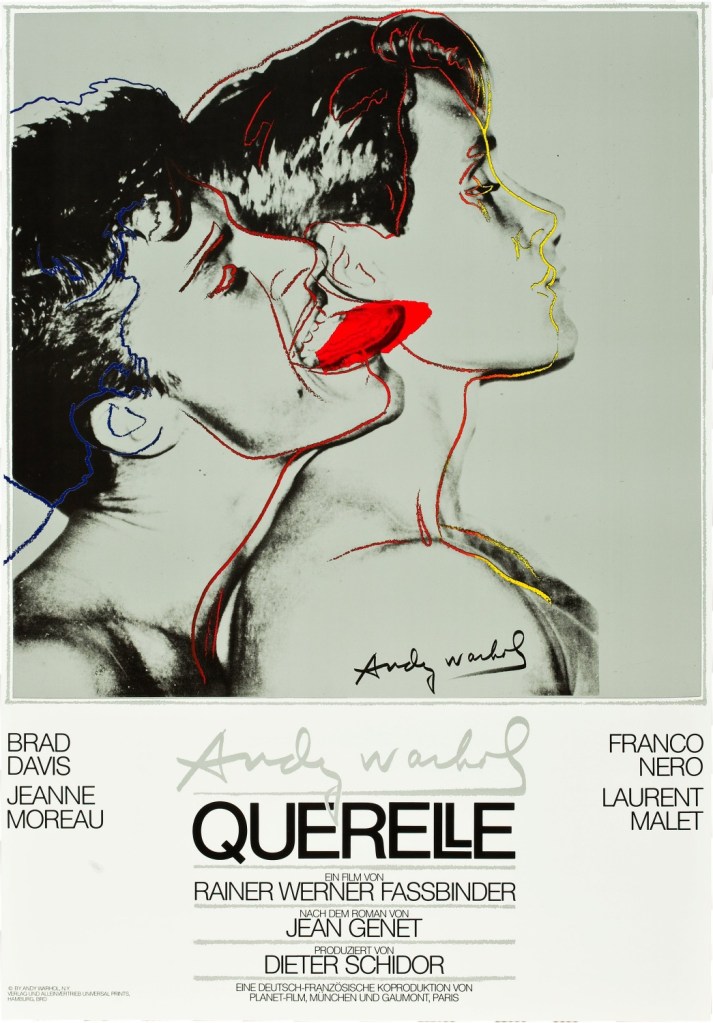

This is the second film Ozon has made from a Fassbinder play, and whereas some directors approach an adaptation as a challenge, attempting to claim a text as their own, erasing the traces of the original author – in the way that Kubrick’s film The Shining supersedes the Stephen King novel from which it was adapted – Ozon’s film is very much a homage to the German director. Peter von Kant is set in Cologne in the early 1970s and the film’s production design emulates the style of Fassbinder’s films from that period. Fassbinder’s films are full of mirrors, windows, screens and frames, paintings, prints and photographs, offering us a visual reminder that what we are looking at is not life, but just a flat screen on the wall, a picture for us to scrutinise and interpret. This is further emphasised by the use of richly coloured fabrics, costumes and lighting, and all of this is on display in Peter von Kant. Ozon’s fannish love of Fassbinder’s work is demonstrated by a brief visual allusion to All that Heaven Allows, the 1955 Hollywood melodrama by German director Douglas Sirk which was the basis for Fear Eats the Soul, and extends to the poster for Peter von Kant, which is based on Andy Warhol’s poster for Querelle (1982), the last film Fassbinder completed before his death from an overdose at 37.

- Andy Warhol’s poster for Querelle (1982)

Like Fassbinder, Ozon wants us to know that we are watching a film and this self-consciousness is underscored by the casting of Hannah Schygulla as Peter von Kant’s mother. Schygulla played Petra von Kant’s lover in the original film and was Fassbinder’s favourite actor, appearing in 23 of his films and TV dramas. This is a way of paying homage to Fassbinder, but Peter von Kant is not a slavish copy of Fassbinder’s film. Whereas Fassbinder’s austere original is quite theatrical, organised in four acts, built around long takes on a single set with little camera movement, Ozon’s film, which is half an hour shorter, is more stylistically dynamic with busy cutting, varied camera angles and mobile camera. The performance style of the actors is also very different. Whereas Fassbinder, who was sometimes a bullying, abusive and pedantic director, demanded a minimal, cool, performance from his actors, the actors in Peter von Kant are much more expressive, to the point where the film sometimes begins to feel like a farce, with the camp excess of a film by Pedro Almodóvar.

Nevertheless, Ozon’s film remains a moving examination of one of the central themes of Fassbinder’s work, the tragic impossibility of romantic love. At one point in The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, as the two lovers are getting to know one another, Karin says to Petra, ‘I love the movies. Pictures about passion and pain. Lovely.’ It is a line that comes straight from Fassbinder’s mouth and, as we see with this film, Ozon understands the cinema in exactly the same way: lovely pictures about passion and pain.