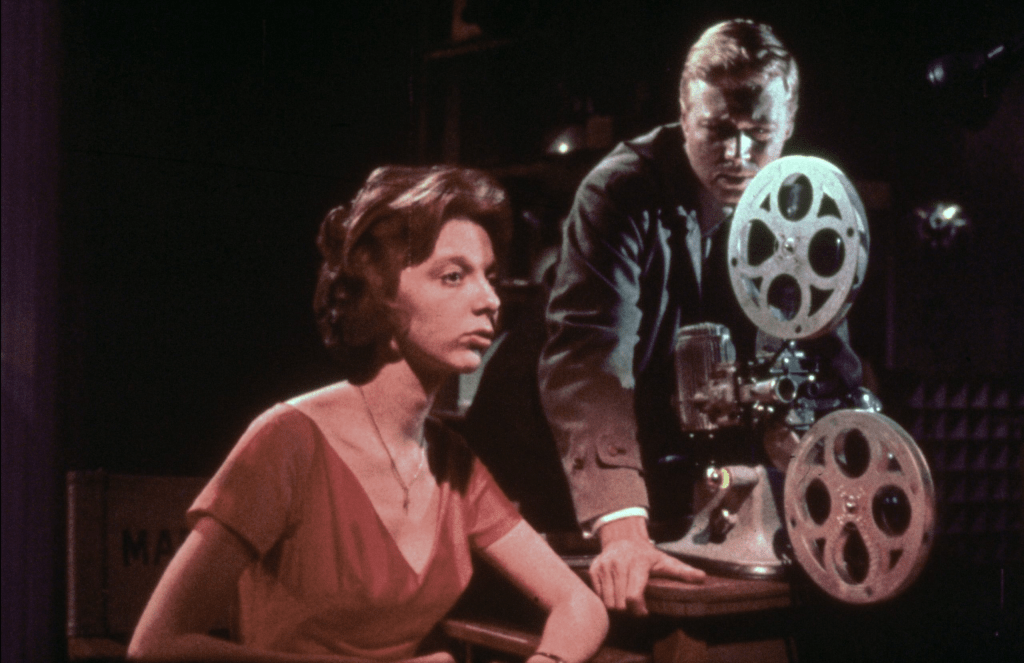

Helen (Anna Massey) and Mark (Carl Boehm) in Peeping Tom

An introduction to the screening of the film at the Dukes cinema, Lancaster, 4/2/24:

Peeping Tom is a late film by Michael Powell, one of the major British directors of the 20th century. He first began making films in the early 1930s, when British studios were specialising in cheap films – quota quickies – that were made to meet the increased demand for British-produced films after legislation was introduced imposing a quota on US imports in order to try to combat the domination of British cinemas by American films. Powell went on to become one of the most celebrated British directors of the 1940s and 1950s, producing films that were highly distinctive in terms of their visual style, blending Technicolor fantasy with realism in a fusion of Hollywood spectacle and European art cinema, and which are shot through with irony, romance and eroticism.

Although he made a handful more films after the release of Peeping Tom in 1960, it is typically discussed as the film that killed his career prematurely. Contemporary reviews of the film were fairly damning – Caroline Lejeune, film critic at The Observer, walked out of the press screening, while the Tribune reviewer wrote, ‘The only really satisfactory way to dispose of Peeping Tom would be to shovel it up and flush it swfftly down the nearest sewer.’ The distributors responded by pulling the film from British cinemas and selling the negative to an American businessman who went bankrupt shortly afterwards, meaning the film more or less disappeared until it was revived in the US in the late 1970s, and re-evaluated as one of his most important films.

Powell himself also blamed the producers for failing to market the film in the right way, and it is notable that when Alfred Hitchock’s Psycho, another film portrait of a serial killer, was released a few months later, the advertising campaign for that film prepared the audience for what they were about to see by exaggerating its sensationalism, turning the release of the film into a culturally significant event. Cinemagoers weren’t allowed into the auditorium once Psycho had begun, for example, and some cinemas even locked the doors in order to emphasise the sense of drama.

Although death and violence are central themes running through Michael Powell’s films, especially those he made with Hungarian immigrant Emeric Pressburger, such as The Red Shoes, Black Narcissus, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, and A Matter of Life and Death, they also offered a reassuringly familiar image of Britishness that is largely absent from this film. Peeping Tom turns its gaze on the seamier side of British society, and it seems that this was not what critics expected or wanted from Powell.

Nevertheless, what makes it one of the most interesting of his films is that, more than any of the others, it is a film about film-making and the image. Peeping Tom reflects upon its own status as a film. It tells the story of a quiet, socially awkward young man, Mark Lewis, who works as the focus-puller in a film studio (in scenes that were shot on location at Pinewood), and for extra cash, shoots pornographic photographs in a makeshift studio above a seedy newsagent. In his spare time, Lewis shoots film compulsively on his small 16mm camera, explaining to several people that he is making a documentary. However, it is revealed almost immediately in the first scene that Lewis is a killer and that his particular predilection is to film women while he murders them. He has built a developing lab and screening room in his house where he watches the films back repeatedly at his leisure. Peeping Tom is not so much a whodunnit as a whydunnit.

This is a film about male violence, but it also makes clear that film-making is, itself, an act of violence. One of the principal pleasures that cinema offers us is the pleasure of voyeurism – of watching others from the invisibility of a dark room without being observed. Thus, it is a complex pleasure that combines the enjoyment of gazing at spectacular, beautiful, fascinating images with the enjoyment of being unobserved and anonymous. This relationship between the observer and the object of their gaze rests upon an unequal power relationship – to be stared at without realising you are being watched is to be exposed and vulnerable, while to be able to look at someone else without them realising they are being studied, is to be secure and in control. The film shows us too, that this is a gendered relationship. The art critic John Berger wrote in 1972 in his analysis of Western visual culture that it is organised around the assumption that, ‘Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves.’ Michael Powell’s film makes clear that the cinema is an intrinsic component of this culture.

Cinema makes Peeping Toms of us all. This is an idea that is as old as cinema itself, as is evident in French film-maker Ferdinand Zecca’s 1901 film, Par le trou de la serrure (aka Peeping Tom), which uses point-of-view shots to show us what a prurient hotel porter sees when he peers into guests’ rooms, but what makes Powell’s film uncomfortable viewing – and helps to explain the critical distaste for it – is that, unlike most films, it reminds us continually that that is what we are. The film opens with a close-up of an eye, shortly followed by a close-up of a camera lens, and then there are several point-of-view shots through the viewfinder of a camera as Mark follows a prostitute up to her room. The shots of the eye and the lens announce that this is a film about looking, and the pov shot aligns us with Mark, as if to suggest that we are complicit in this looking – that we enjoy it just as much as he does.

The theme of the violence of the gaze is reiterated at various points during the film, and is emphasised towards the end when we learn that Mark’s late father was a biologist who was working on the subject of scoptophilia when he died. Scoptophilia is a concept explored by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud in the early 20th century to describe the sexual pleasure that comes from looking at arousing objects or images, rather than from sexual activity itself – for Freud an obsession with looking can become an uncontrollable perversion where sexual pleasure can only be derived from looking, and this seems to be Mark’s affliction. Film theorists have often suggested that this helps to explain why watching films is so addictive and so enjoyable, and why it is different from other storytelling forms – it stimulates and satisfies this desire to look.

As well as a film about film-making, this is also a film about fear – a preoccupation that Mark shares with his father. Although it belongs to a tradition of horror films (a connection that is underlined by Viennese actor Boehm’s performance, which often recalls that of Peter Lorre, who made a career out of playing sinister characters and killers (including one of the first cinematic serial killers in M)), it doesn’t rely on shock and suspense. It is more interested in playing with ideas. The film was written by Leo Marks, who trained code-breakers during WW2, and who went on to write plays and filmscripts. He and Powell had intended to make a film about Freud, but when they heard that Hollywood director John Huston was working on a biopic, Marks suggested Peeping Tom and, appropriately enough, the film invites us to scrutinise it as if it is a code that needs deciphering or a patient who needs diagnosing. Mark’s neighbour Helen, who happens to be writing a children’s book about a magic camera, tells Mark, ‘I like to understand what I’m shown’, but whereas a mainstream entertainment film is typically designed to give us that pleasure – the pleasure of understanding – the pleasures of this film are a little different. Like the detectives investigating the murders, we need to look hard and piece together the clues, and it is peppered with them, such as the briefest glimpse of Powell himself, playing Mark’s father, or a cameo from Moira Shearer playing an unsuccessful extra dancing around an empty film studio dreaming of being a star. In reality, Shearer was the star of The Red Shoes, perhaps Powell’s most famous film about a professional ballet dancer dreaming of stardom, and another film about obsessive creators.

Populated by characters who look – psychoanalysts, scientists, detectives, film-makers and photographers – Peeping Tom is thus, also, a film that rewards looking. It depicts post-war London as a rather grim environment that is not so far removed from the mise-en-scène of the kitchen sink films of the British new wave. Like films such as Room at the Top and Saturday Night, Sunday Morning, it offers glimpses of a society that is marked by sexual repression, moral hypocrisy and rigid boundaries between classes, but like other films by Michael Powell, it is also full of smart, perceptive female characters who often have a better understanding of what’s going on than do the self-important men around them. The cinematographer was Otto Heller who shot the 1955 Ealing film, The Ladykillers, and he ensures Peeping Tom is as beautifully lit and as full of colour as any of the big budget spectacles produced by Powell. Although this film deals with some disturbing themes, it has as much in common with the black humour and gothic camp of Ealing comedies or Hammer horror films as it does with the bleak slasher films that are part of its legacy. While it’s unsurprising that professional film critics may have found the film uncomfortable, there is a great deal to enjoy in this dark film.

Reference:

John Berger (1972), Ways of Seeing, BBC/Pelican: London.