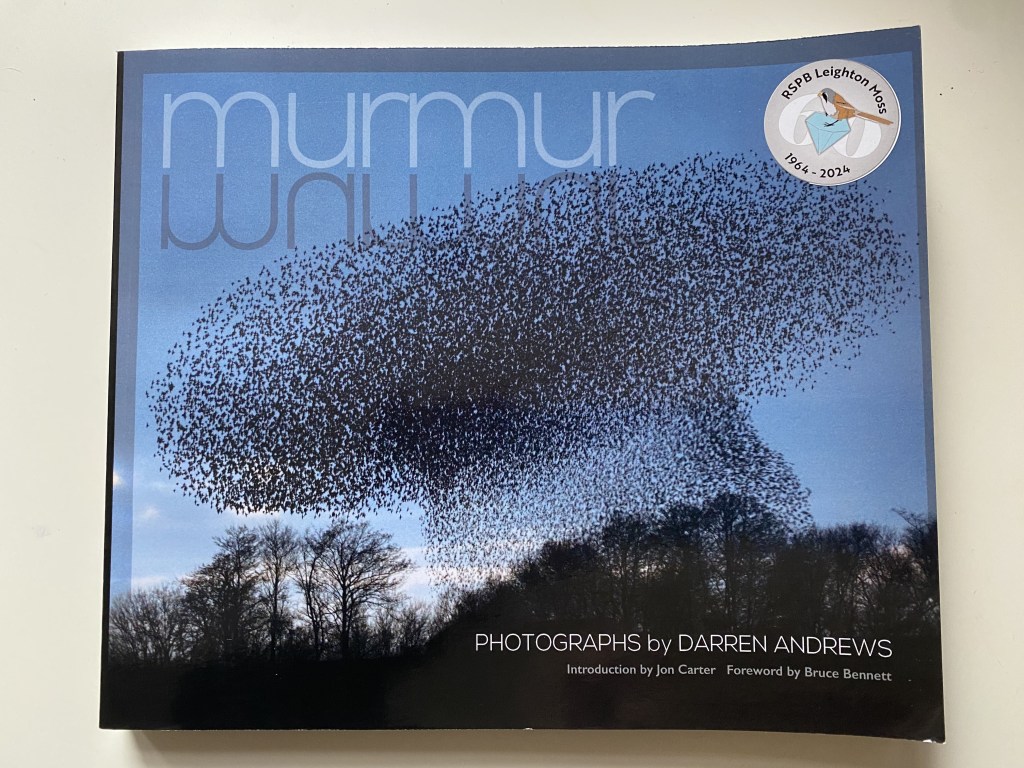

(This is the short introduction I wrote to Murmur (2024) a new edition of a book by Lancaster-based photographer Darren Andrews of strange and beautiful photographs of starling murmurations, some of which are included below)

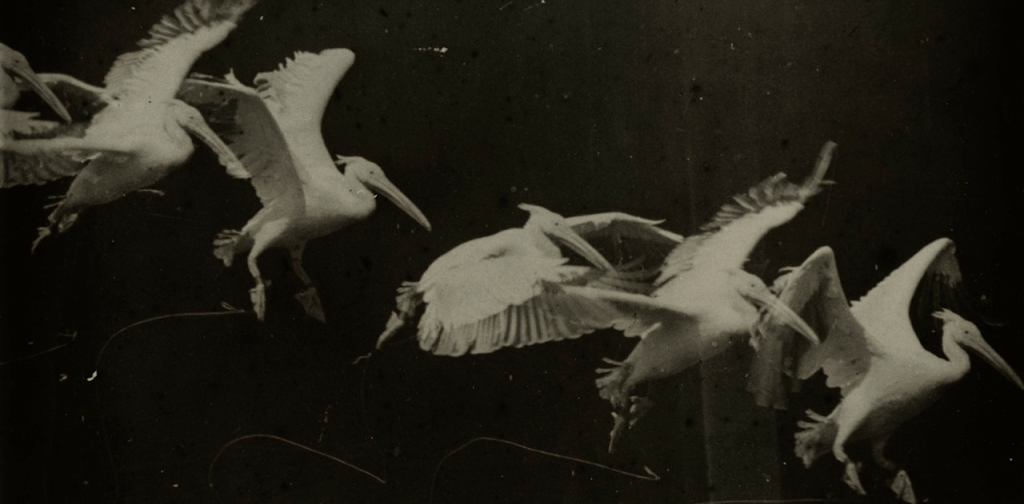

In the late 19th century French physiologist Etienne-Jules Marey became preoccupied with the challenge of studying movement, convinced that medical knowledge and diagnostic accuracy were limited by a reliance on the analysis of static bodies. He developed a series of mechanical devices for recording bodily motion, producing a portable version of the blood pressure monitor, the sphygmograph, that could also record the tiny regular movements of the skin surface caused by blood pulsing through arteries. However, in the late 1870s, inspired partly by the famous sequential photographs of British photographer Eadweard Muybridge, he began to focus on photography’s potential as an analytical tool. Exploiting the increasing sensitivity of photographic emulsion that allowed photographs to be exposed in thousandths of a second, Marey began to produce what he called chronophotographes, in which a series of separate photographs taken a fraction of a second apart are exposed on a single plate. These images record an action, such as a man jumping over a hurdle, riding a bicycle or pole-vaulting, as a series of successive frozen moments.

- A ‘chronophotographe’ by Marey of a heron in flight (1883)

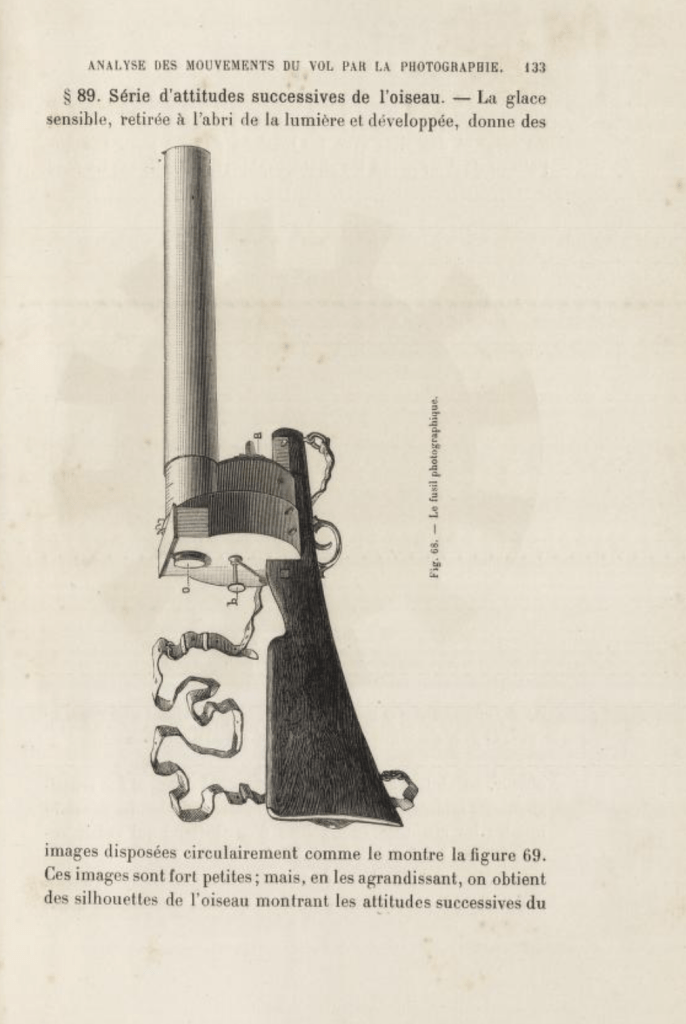

Marey was particularly interested in flight, even constructing a rotating arm to which he could attach a bird so that he could observe it flying, and in 1882 (as if anticipating the adoption of the hunting term, ‘snapshot’ to describe the process of firing off photographs rapidly), he invented the fusil photographique (‘photographic rifle’), a camera loaded with a spinning glass plate that enabled him to photograph birds as they flew through the air. ‘You aim at the bird like a hunter would’, he explains in his 1890 volume, The Physiology of Movement: The Flight of Birds, alongside an illustration of the hybrid camera-gun (Marey 1890: 132).

- Marey’s ‘fusil photographique’

What Marey recognised, of course, was that photographs allow us to see things that our invisible to our eyes. In his 1931 essay, ‘Little History of Photography’, German philosopher and cultural theorist Walter Benjamin, almost certainly familiar with the work of Marey and Muybridge, observed that this capacity of photography to show us a world that is both visible but imperceptible, is a defining property of the medium:

‘Whereas it is a commonplace that, for example, we have some idea what is involved in the act of walking (if only in general terms), we have no idea at all what happens during the fraction of a second when a person actually takes a step. Photography, with its devices of slow motion and enlargement, reveals the secret. It is through photography that we first discover the existence of this optical unconscious, just as we discover the instinctual unconscious through psychoanalysis’ (Benjamin 2005: 511-512).

Darren Andrews’ photographs of murmurations are a perfect illustration of this phenomenon. In capturing frozen moments they reveal in these formations an extraordinarily complex, uncanny beauty that the unaided eye is incapable of registering, except as a fugitive, blurred impression. Like visual echoes of Rorschach inkblots, the abstract shapes of flocking starlings are an invitation to look for meaning, triggering different associations in different spectators. For me, there is something apocalyptic and threatening in the way that these morphing black forms shot in the fading light of dusk suggest devastating locust swarms, or CGI representations of aliens or monsters in science fiction and fantasy cinema. Utterly indifferent to the presence of spectators, these manifestations of leaderless, collective decision-making offer us an image of a post-human world in which people are an irrelevance.

In capturing moments of such complex, dynamic movement, these photographs also tell us something about the profound beauty of impermanence. According to the RSPB, the UK population of starlings has declined rapidly since the 1970s, for reasons that remain a mystery, and so there is a additional poignancy to these photographs that depict arrested moments of rapid change, since they are document a phenomenon that might well vanish in a few decades. The speed at which climate change is accelerating has brought home to us how fragile the natural environment in which we live is, and Darren’s images of mutability are a powerful symbol of this condition. They show us a state of nature in constant flux, a delicate world in which the vast, impossibly intricate, and apparently solid structures created by these birds constantly shift, flicker, convulse…. and then suddenly melt into thin air.

References:

Walter Benjamin, 2005. Selected Writings, Volume 2, Part 2: 1931-1934. Eds. Michael W Jennings, Howard Eiland, Gary Smith. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Etienne-Jules Marey, 1890. Physiologie du Mouvement: Le Vol Des Oiseaux. Paris: Librairie de L’Académie de Médecine