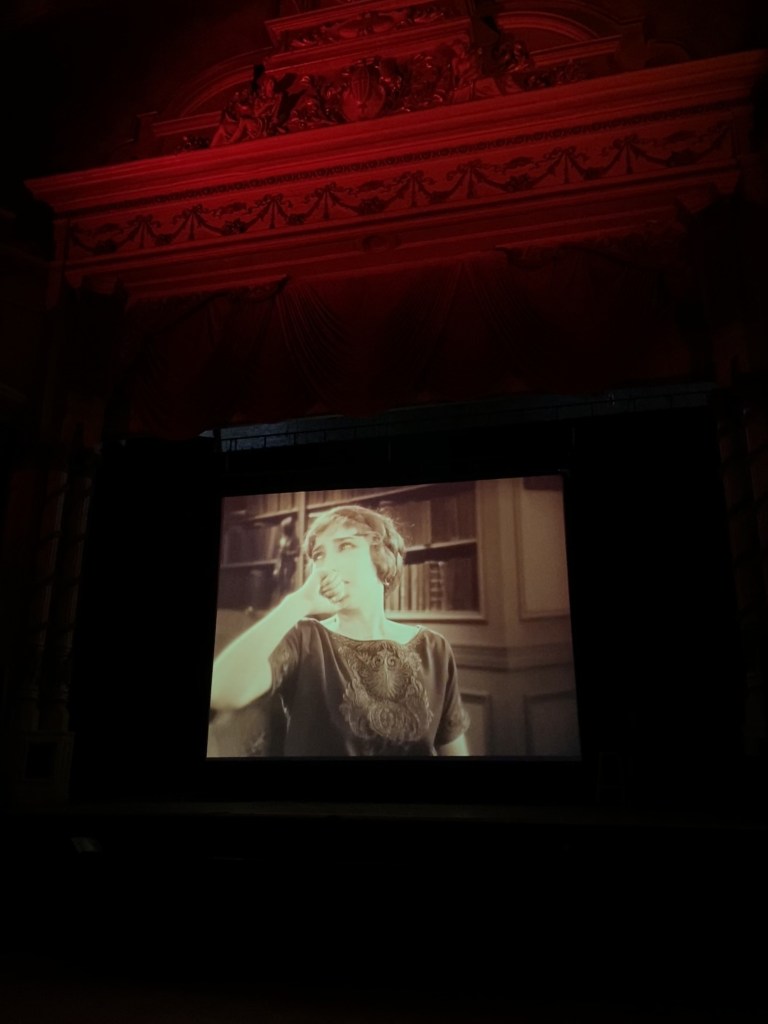

- Bessie Love in The Lost World

A real pleasure this weekend to attend the ‘Silents by the Sea’ film festival put on by the Northern Silents organisation at the Winter Gardens Pavilion in Morecambe, a grand variety theatre built in the 1890s, and currently undergoing restoration. It’s a particularly apt setting since some of the films screened over the weekend may well have been shown in the venue on their release, although as I learnt from chatting with local historians and Vanessa Toulmin in between sessions, the Winter Gardens was a mixed cine-variety venue and there were actually another seven cinemas in the town.

The two-day event is possibly unique for the emphasis it places on the music accompanying the screening of silent films. This was exemplified by a panel discussion with some of the contributing musicians discussing their approaches to improvisation, the paradoxical idea that the most effective performance is the one that goes un-noticed by the viewer, the importance of silence in music, and the question of whether it’s possible to play a wrong note.

The first day featured sold-out screenings of two Chaplin shorts, By the Sea (1915) and The Cure (1917), accompanied with apparent effortlessness by pianist/composer Neil Brand. This was followed by a screening of The Kid (1921), with a small orchestra, the Northern Silents Sinfonia, giving a sumptuous performance of Chaplin’s own score that brought out the emotional power of the film. Much of the second day was given over to screenings of Méliès films, alongside the extraordinary Symphonie Bizarre by Segundo de Chomón, and these were accompanied by improvising musicians playing in varying configurations from solo piano, synth and percussion duo, through to jazz band and choir. A number of these performances involved professional musicians playing alongside amateurs from the local area – as well as audience participation for one film – and in this way it made a clear point both about the participatory, democratic nature of music, and also about the participatory, hybrid nature of cinema before synchronised sound, in which every screening was a singular, live event.

The closing session was a screening of a recent restoration of the feature film, The Lost World, which was accompanied by the Frame Ensemble, a superb improvising quartet led on piano by the festival organiser and MC Jonny Best. I gave the introduction to the film, which is included below, and am now looking forward impatiently to a follow-up event next year.

- The Lost World on screen in the Winter Gardens

Introduction to The Lost World 9/6/24

The Lost World (Hoyt, 1925) is an adaptation of a novel by Arthur Conan Doyle, which was published in 1912. It was the first in a series of stories about an irascible, eccentric Scottish scientist, Professor Challenger, who is captured perfectly in the film by the American actor Wallace Beery. By the time he made this film in 1925, Beery, who would go on to become an Oscar-winning star, had established himself playing thugs, villains and comic characters, and his portrayal of Challenger, a bear of a man with a habit of assaulting journalists, combines these elements very effectively. The film tells the story of an expedition led by Challenger to the remote interior somewhere between Peru, Brazil and Colombia, where the explorers find an isolated plateau still populated by prehistoric creatures that should have died out millions of years earlier.

This is the first of several film adaptations of the novel, as well as TV and radio series, but it has also been followed by many films on the similar theme of humans coming into contact with dinosaurs from the absurd Hammer studios film One Million Years BC (Chaffey, 1966) through to last year’s 65 (Beck, Woods), about an astronaut who crashlands on prehistoric Earth. The most obvious legacy, however, is the Hollywood franchise that began with Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster, Jurassic Park (1993) and its sequel, The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997). The latest title, Jurassic World Dominion (Trevorrow), was released in 2022 and grossed over $1bn, which suggests that the scenario of people living alongside dinosaurs remains fascinating almost a century after this afternoon’s film.

Like the Jurassic Park films, this is a Hollywood special effects extravaganza, described as a ‘super-production’ by First National, the studio that made it. The film follows the narrative architecture of Conan Doyle’s novel very closely but introduces some significant changes that give it a much more contemporary feel than the book. There are four key characters undertaking the expedition: Challenger himself, Prof. Summerlee, a rival scientist convinced Challenger is a liar or lunatic, Sir John Roxton, an aristocratic big game hunter who is along for the adventure, and young reporter Edward Malone, who is looking for a scoop. The first key change introduced by screenwriter Marion Fairfax is the addition of a woman to the group, Paula White, the daughter of an explorer lost on an earlier expedition. In a classic Hollywood story-telling strategy, this enables a romantic subplot to be threaded through the film. A second significant change is that whereas in the novel, the explorers encounter groups of prehistoric humans whom they set about enslaving and exterminating, this genocidal, colonial subplot has been almost entirely removed from the film. And, as we’ll see, the third key change is that the novel’s low-key finale is scaled up for a spectacular cinematic climax.

One of the films most directly inspired by The Lost World is, of course, King Kong (Cooper, Schoedsack), released 8 years later in 1933. The scenario is broadly similar – humans encountering monstrous creatures in a remote jungle – and although King Kong is a sound film, it is also stylistically similar. One of the reasons is that Willis O’Brien, the technician responsible for the stop-motion animation in King Kong, was almost solely responsible for designing and filming the dinosaurs in The Lost World. O’Brien hired an art student, Marcel Delgado, to sculpt around 50 miniature model dinosaurs which were mostly filmed on sets about six feet across and four feet deep, although there is one scene where we see a number of dinosaurs grazing on a wide plain that was shot on a much larger set. Both the sets and the models are beautifully intricate; O’Brien was a very skilful animator who pays a great deal of attention to expressive movement, depicting the creatures with such delicacy that we can even see them breathing. Stop-motion animation was not a new technique in 1925, but to make it such a significant component of the film was an innovative, risky move and so it’s unsurprising that much of the contemporary commentary on the film praised the special effects. Indeed, Marion Fairfax was apparently tasked with writing the screenplay in such a way that, if the animation sequences didn’t come off, the film could still be completed, so they shot considerably more story material than is included in the final film (which may explain why one character has their arm in a sling for no apparent reason). What makes these animated sequences so effective is that they are combined almost seamlessly with live-action footage using matte shots so that 100 years later, it remains a technically impressive film in which it’s sometimes very difficult to see how the shots were achieved.

Although the film is successful in modernising Conan Doyle’s novel, there are nevertheless some elements of this film, such as a minor character called ‘Zambo’, a servant portrayed here in blackface, which remind us this is a film from a century ago, and that to watch it is to visit a lost world in a different sense. At the same time, the vivid colour of this restoration in which the original tinting can be seen in its full glory, brings this film into the present, and in a year in which the five highest grossing films so far are fantasy films featuring monsters or impossible creatures – Dune 2 (Villeneuve), Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire (Wingard), Kung Fu Panda 4(Mitchell), Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes (Ball), and Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire (Kenan) – it’s hard to see how The Lost World could feel more contemporary.