A book within a book: A Wheel Within (2023)

One of my key inspirations when I studied fine art as an undergraduate, was the work of British artist Tom Phillips, and in particular, his open-ended ‘Humument’ project, a treatment of an unremarkable Victorian novel, called A Human Document, which Phillips found in a second-hand bookshop near his house. The Humument project involved over-writing, painting, drawing and printing on, collaging, scorching, and slicing up the pages of that book to produce new narratives, characters and meanings. Over the course of his career he produced several complete versions of the treated novel (the first published in 1970, the final edition in 2016), and material from it is scattered across his body of work, including the graphic score of an 1969 opera, Irma, produced in collaboration with composer Gavin Bryars and writer Fred Orton (who happened to be one of my undergraduate lecturers, although I was unaware of the connection at the time).

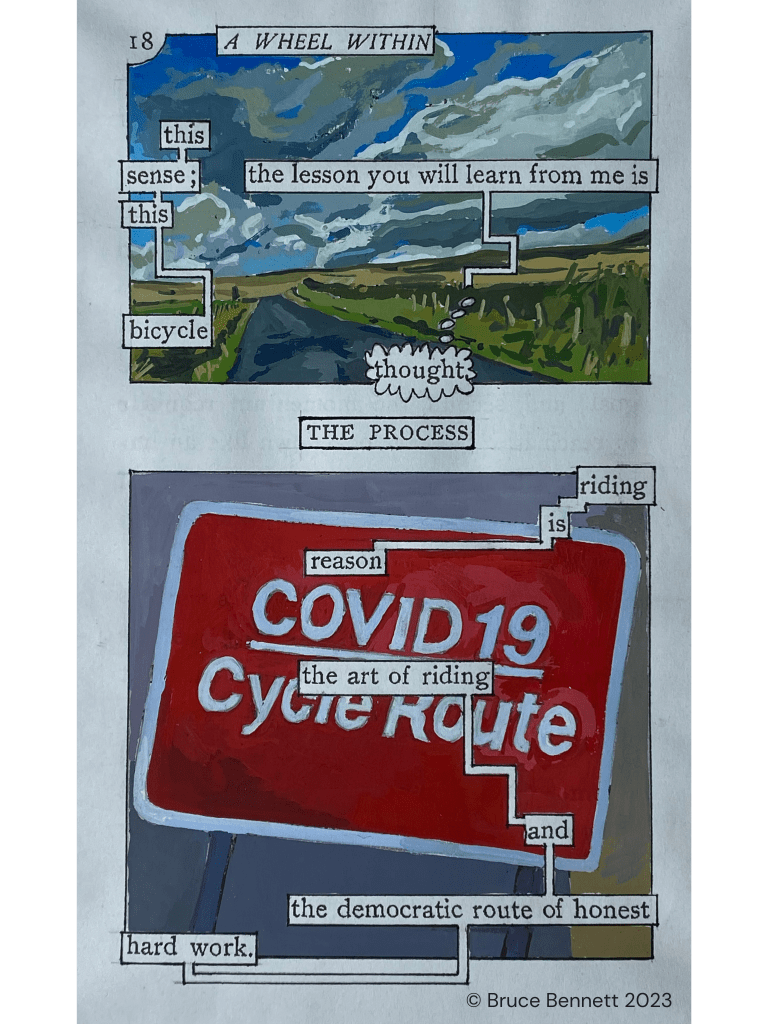

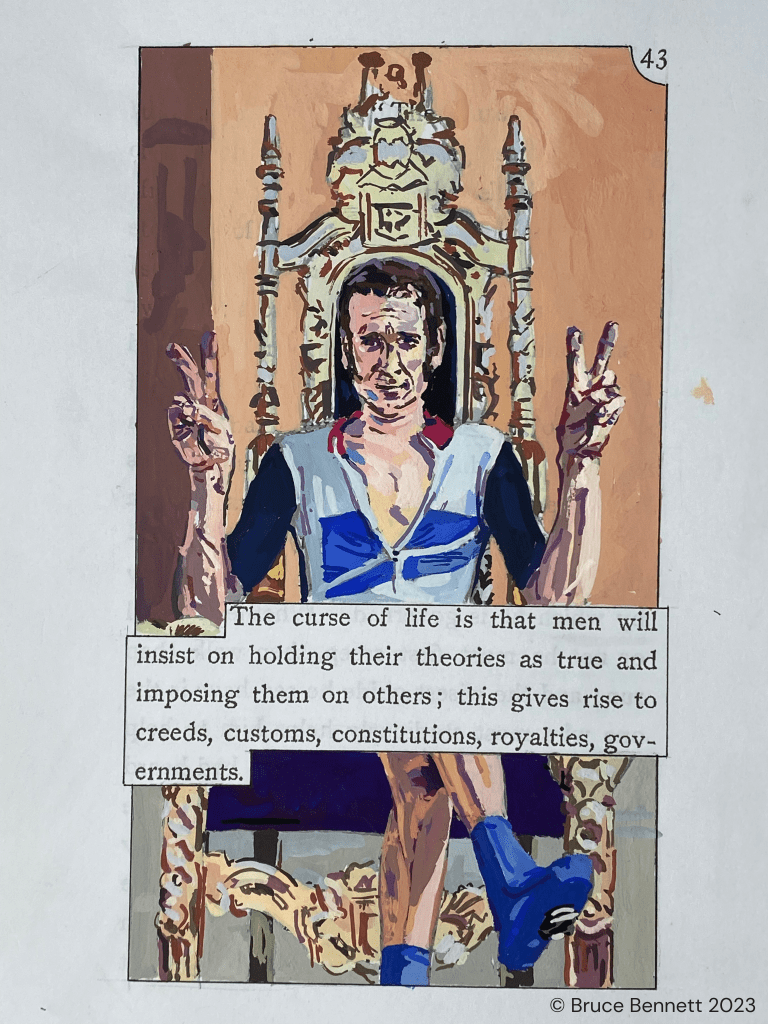

Phillips’ work is inspired by the Duchampian avant-garde practice of making art from objets trouvés, and avant-gardist practices of using chance to generate unexpected and suggestive combinations of images and text, an approach that invokes the surrealist parlour game ‘exquisite corpse’, the music of John Cage, and the cut-up style of writing devised by William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin. Alongside the influence of experimental art, Phillips’ work also draws on the heterogeneous visual style of advertising, film and TV and, most of all, the comic strip, so that A Humument can be thought of as an unconventional graphic novel.

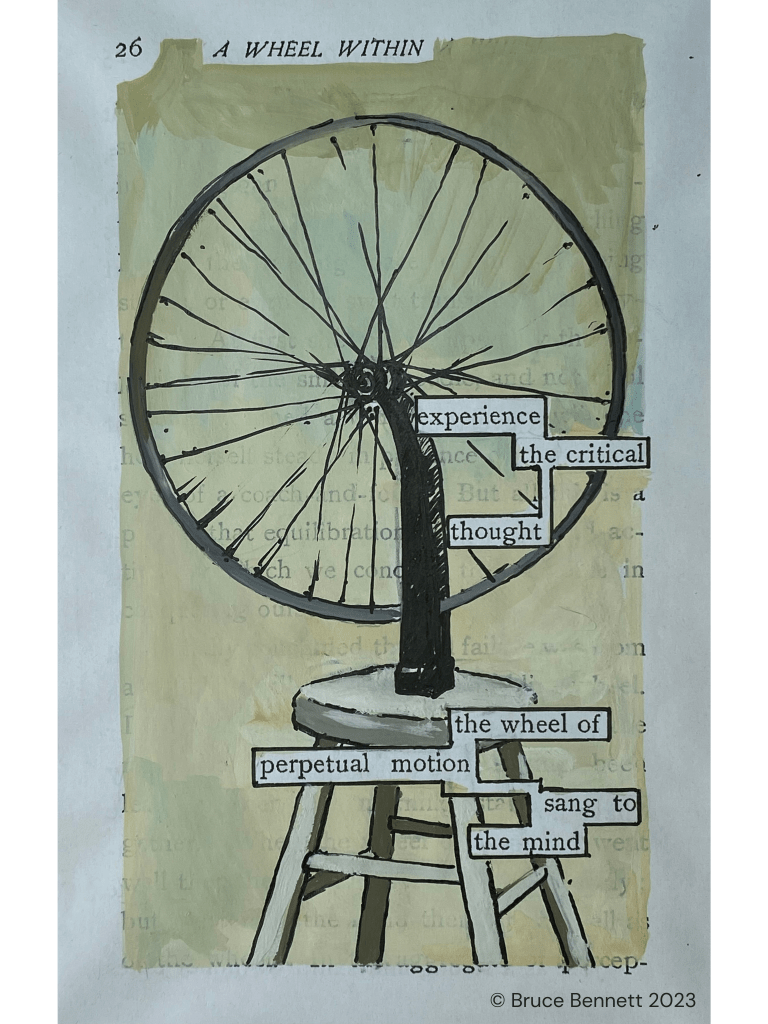

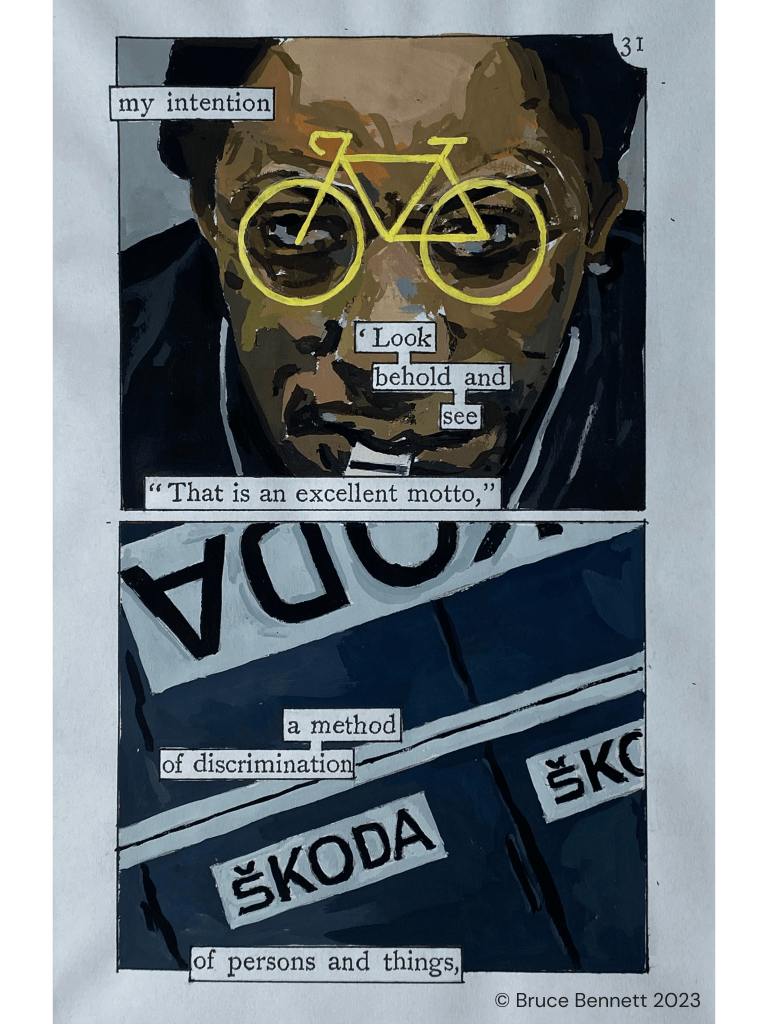

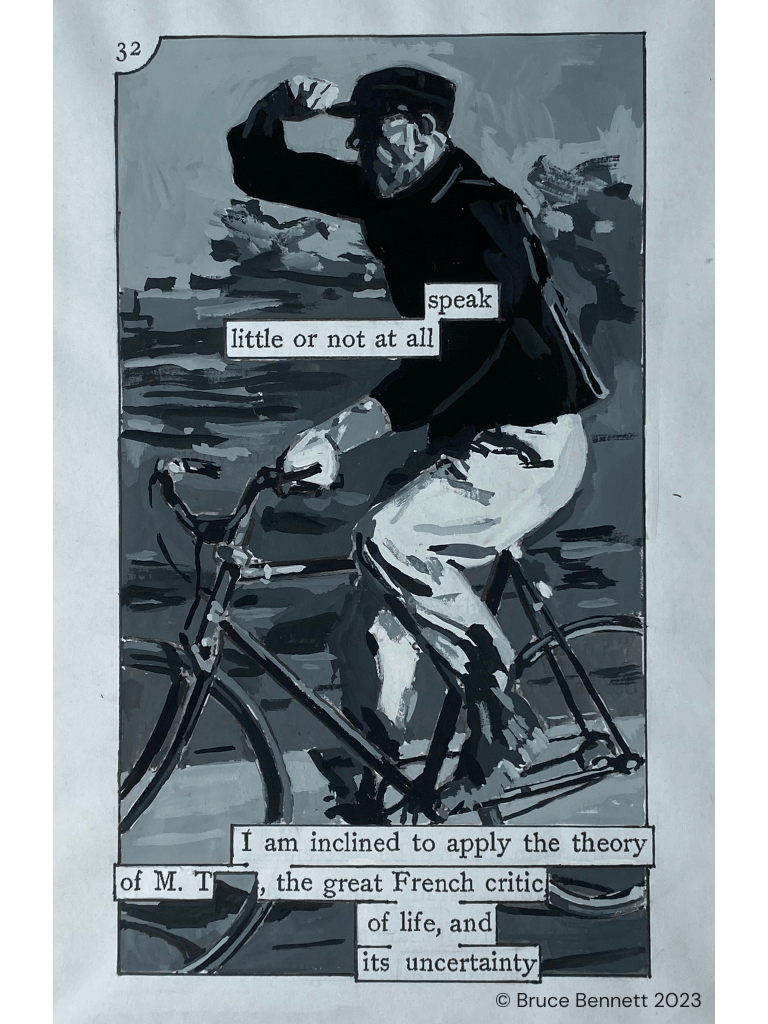

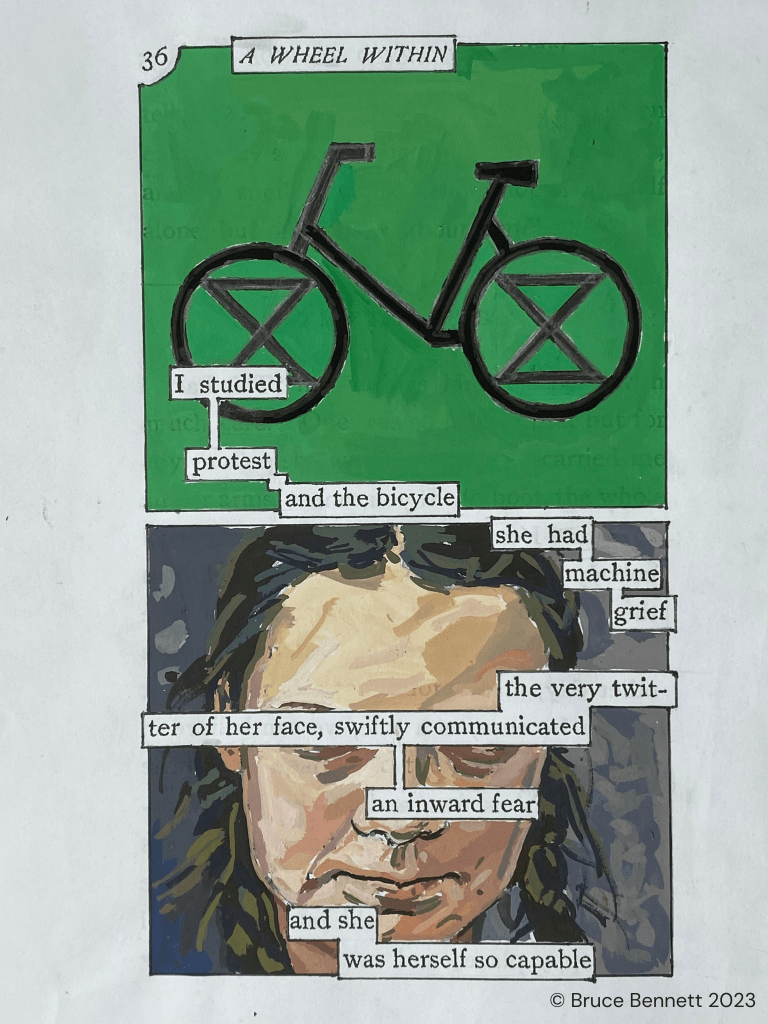

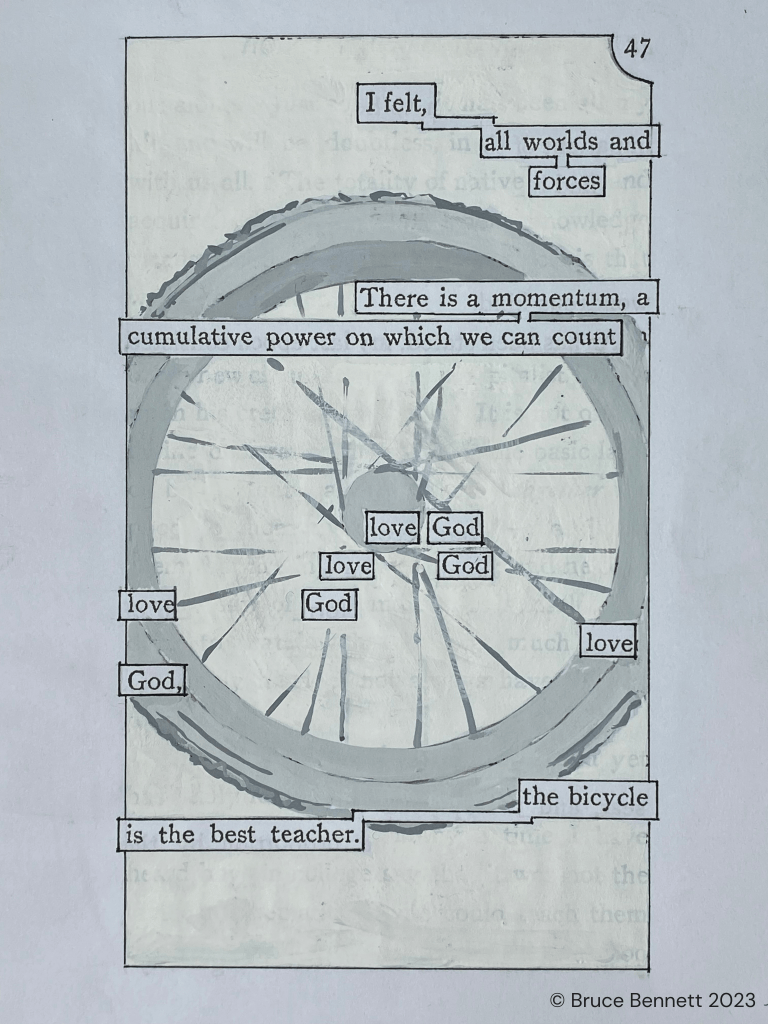

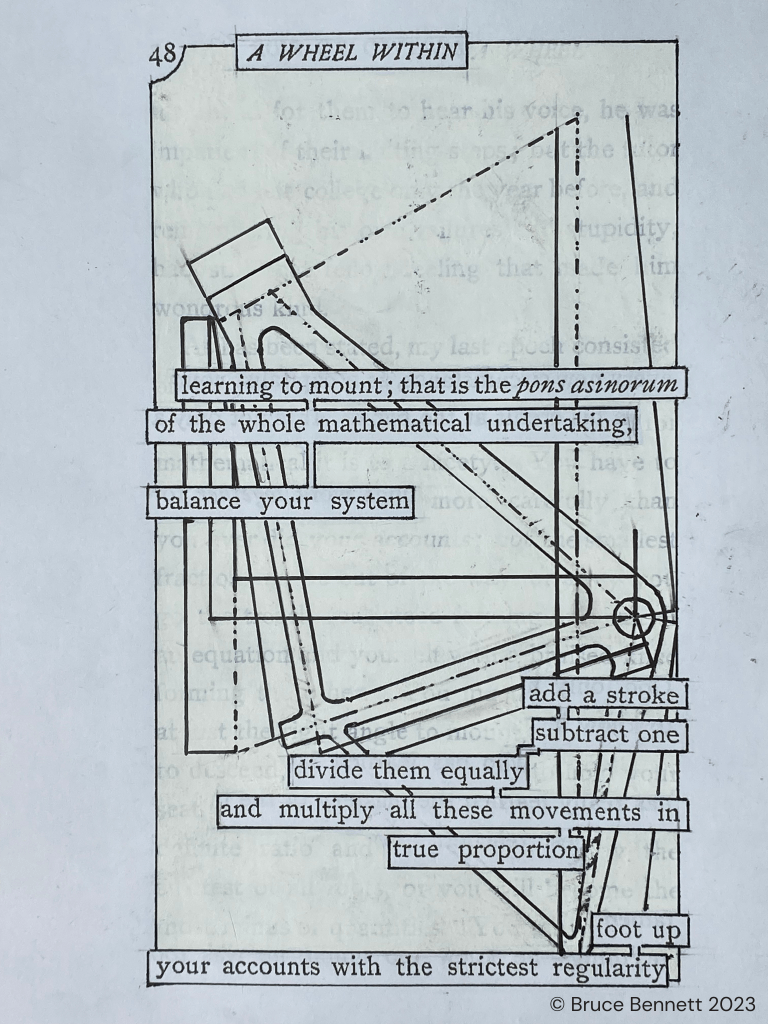

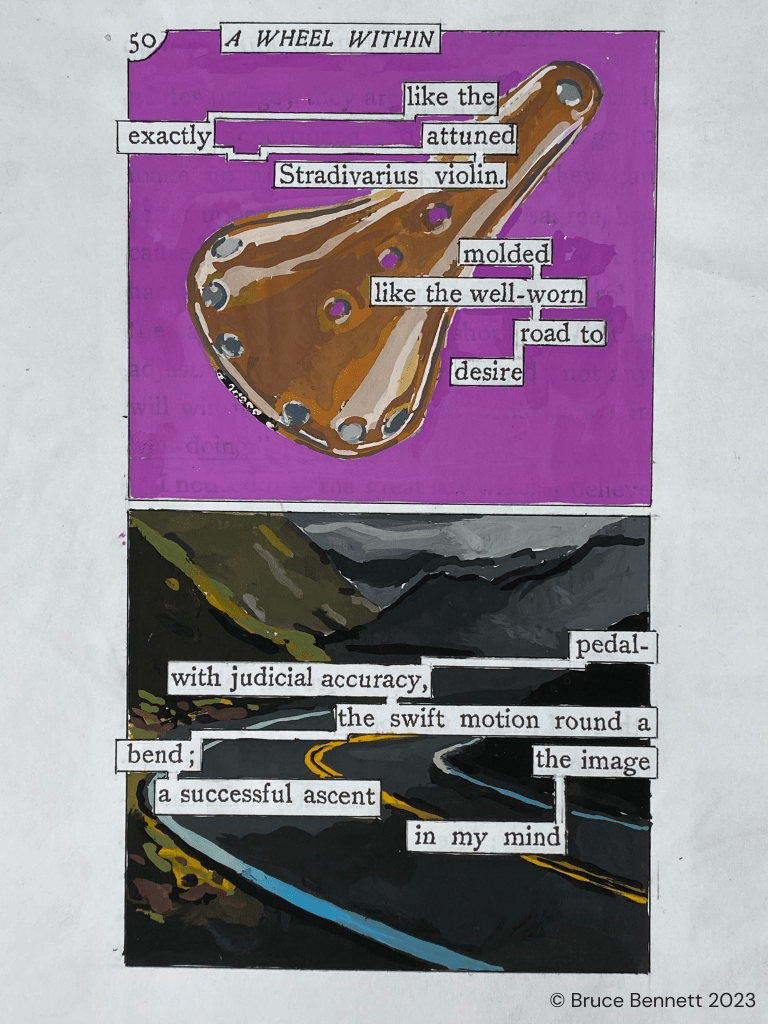

By isolating certain words on the page, and drawing, painting, printing or collaging over the rest of the page, Phillips finds new characters, scenarios and narratives within the frame of the book. As well as a technique for generating images, I think it can also be understood as an analytical technique, a method of creative close reading that homes in on aspects of the text that might be missed by more conventional methods of critical analysis.

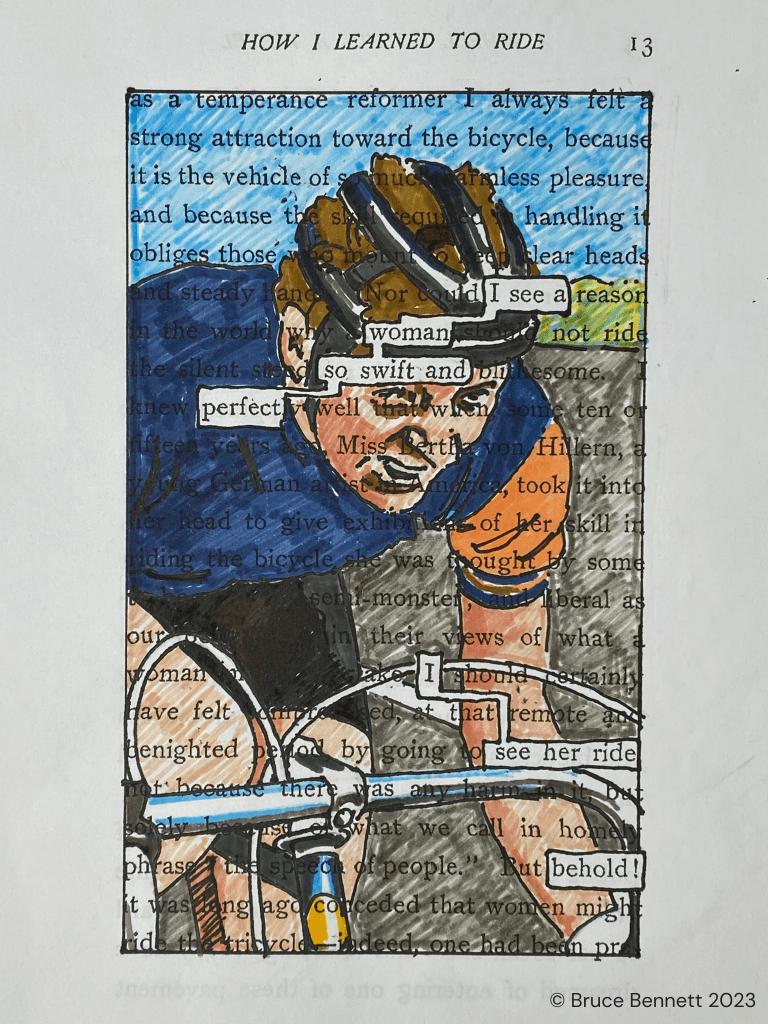

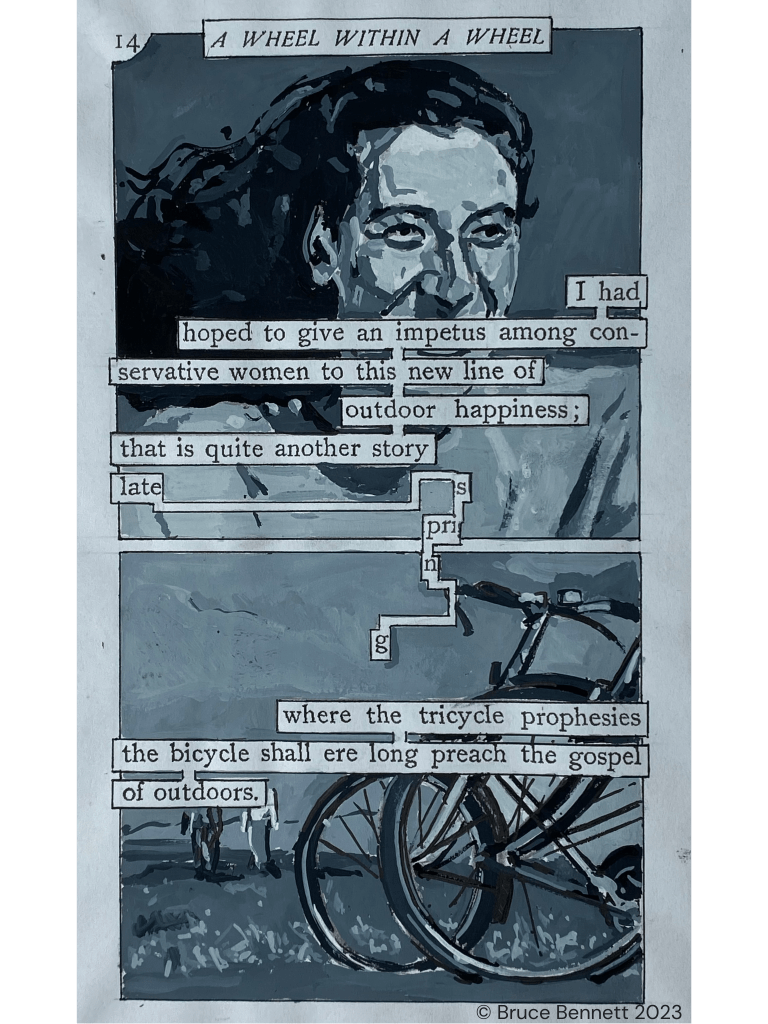

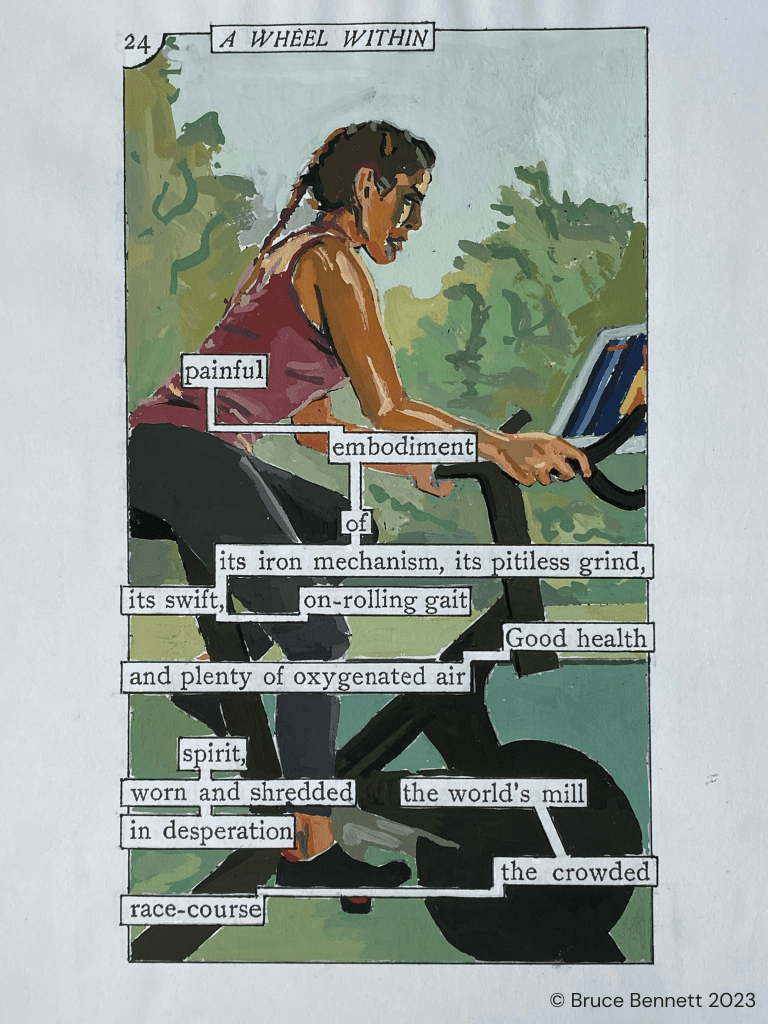

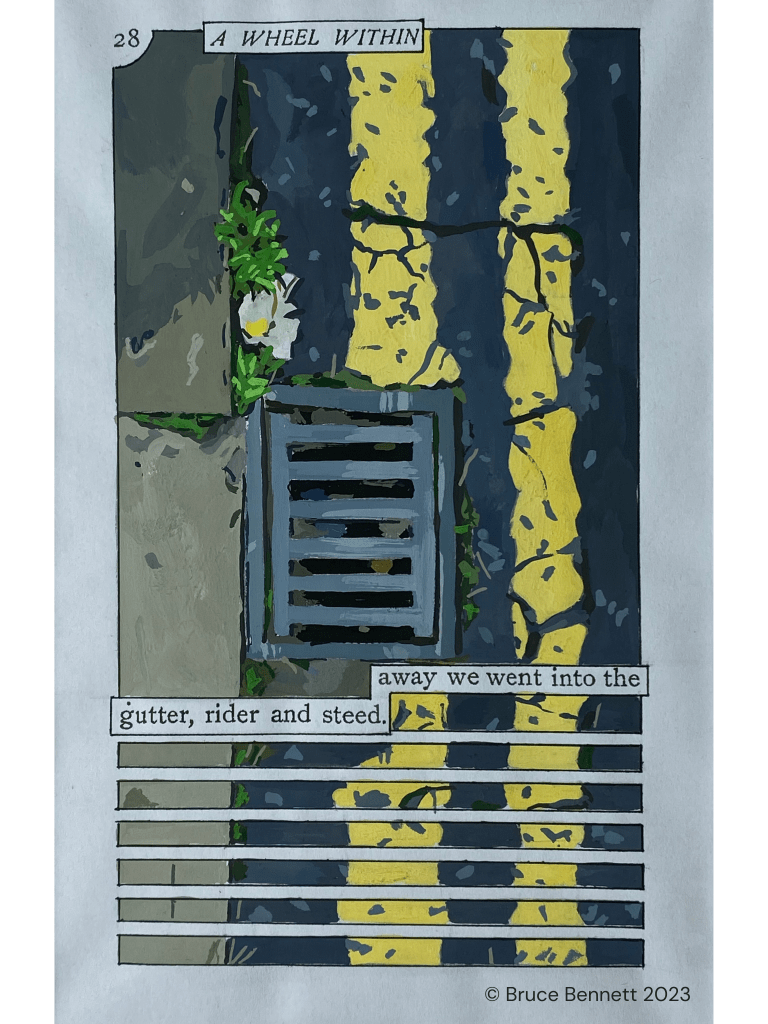

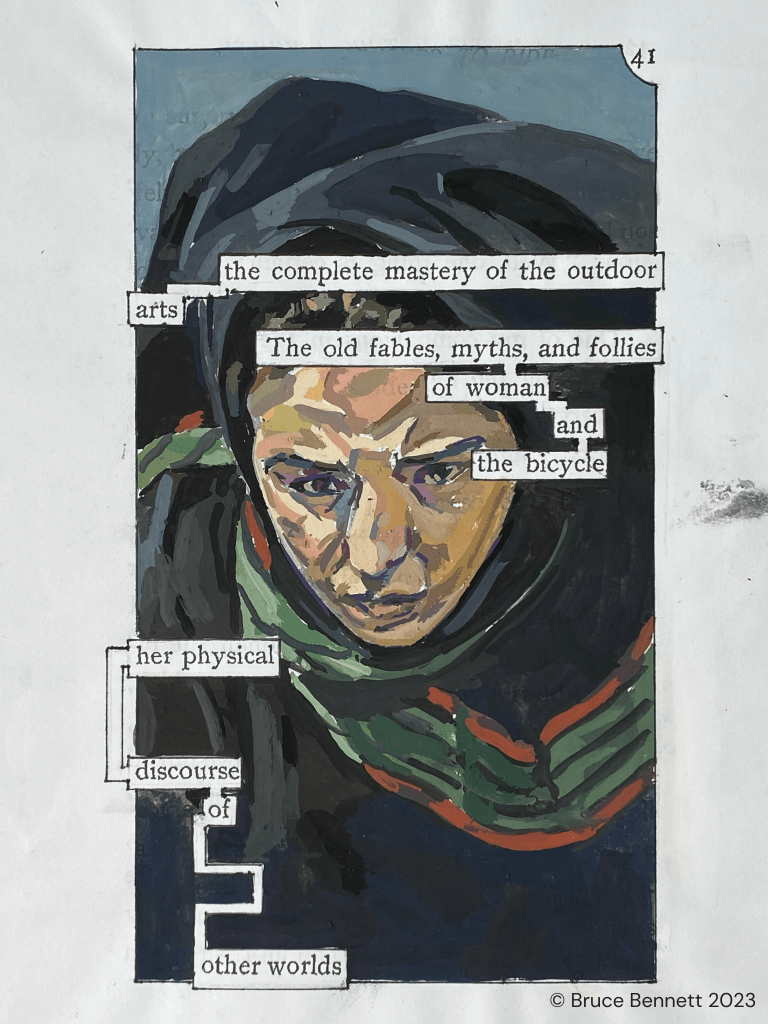

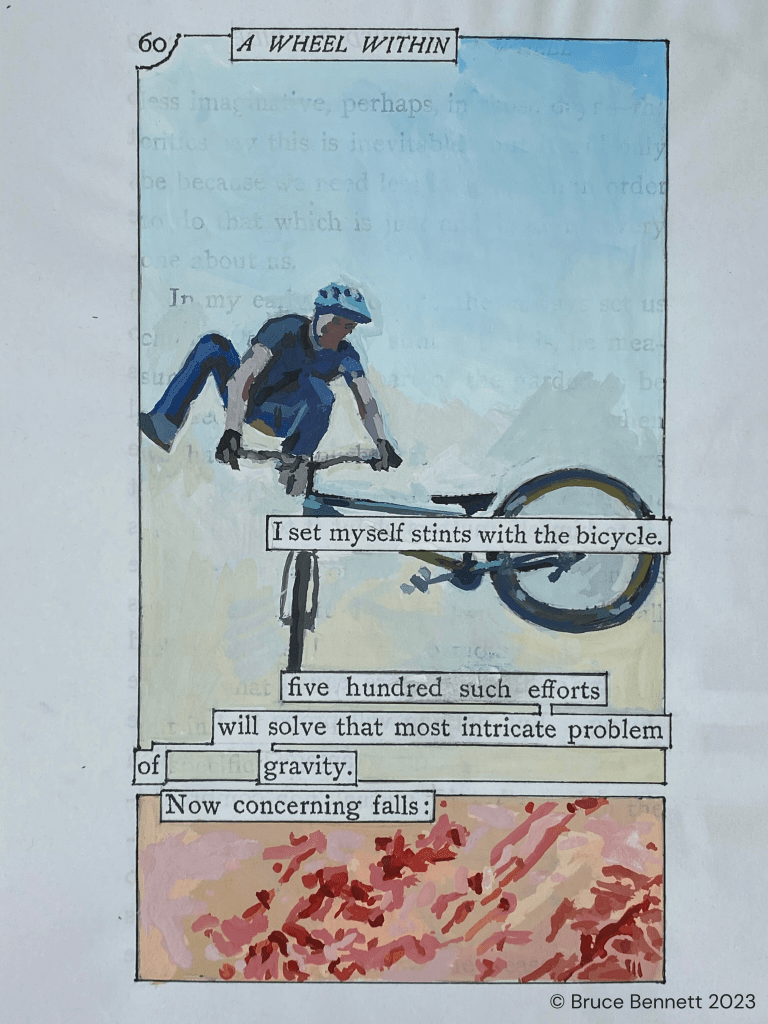

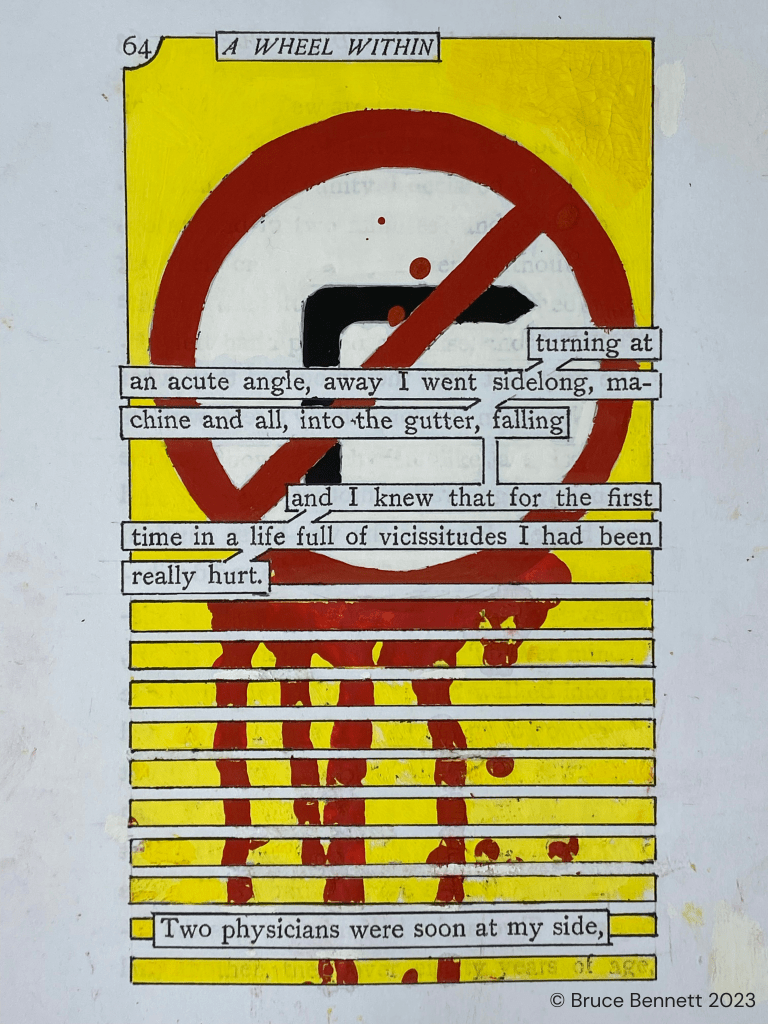

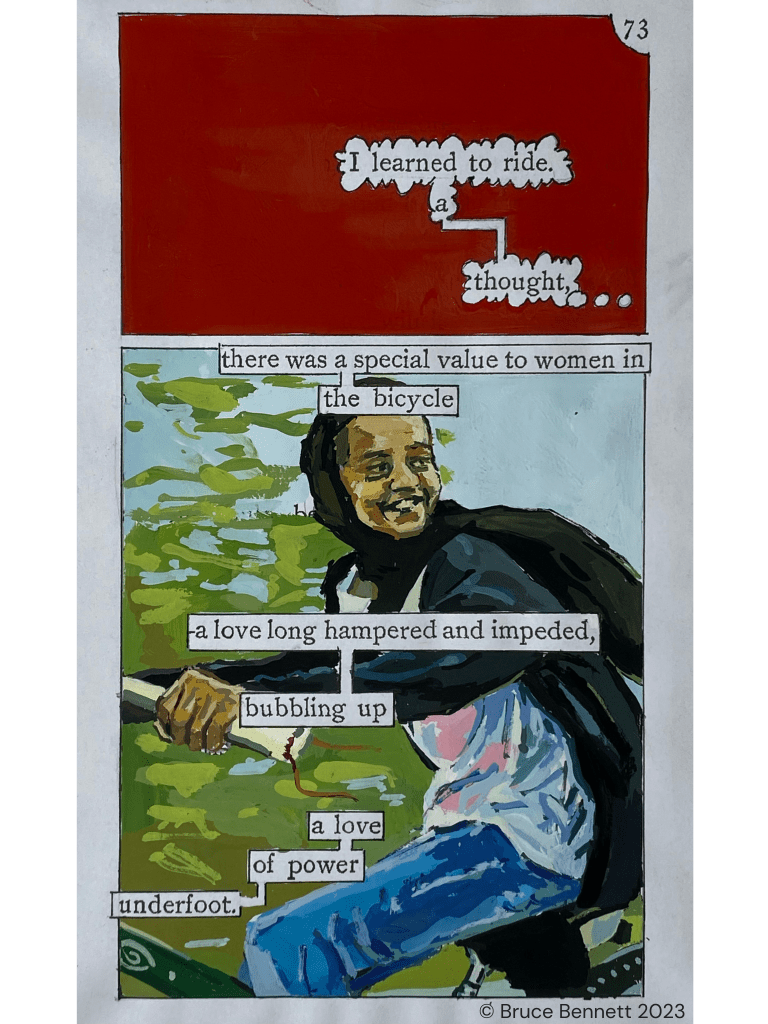

One of the most striking books I came across while writing my book, Cycling and Cinema, was the 1895 volume, A Wheel within a Wheel by American suffrage campaigner and educator Frances E. Willard. Published three years after The Human Document it is an autobiographical account of the transformative experience of learning to ride a bicycle as a middle-aged, middle-class woman, illustrated with some wryly comic photographs of Willard in the saddle. It is not particularly well-known but I think this short book is one of the most important examples of early cycling literature. It is angry and funny, moving, poetic and profound. It proposes that riding a bike is a liberatory political act for women confined by the constraints of bourgeois femininity, and, more broadly, that it can radically reconfigure our relationship with the physical world around us. As she writes, ‘I realized that no matter how one may think himself accomplished, when he sets out to learn a new language, science, or the bicycle he has entered a new realm as truly as if he were a child newly born into the world’.

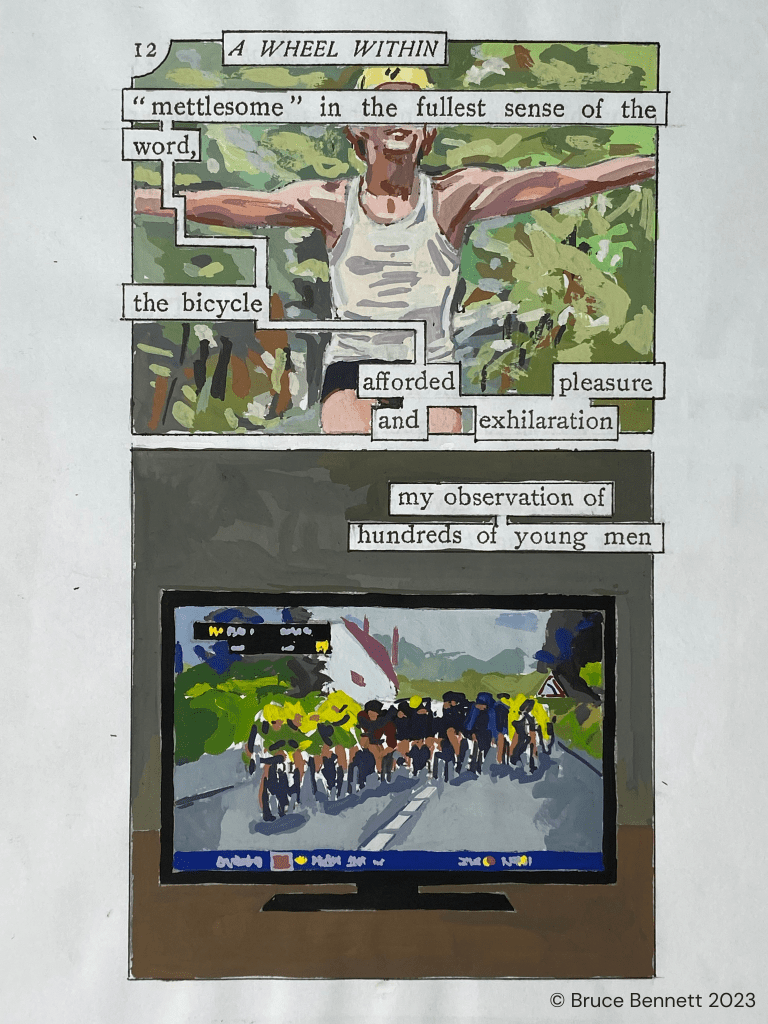

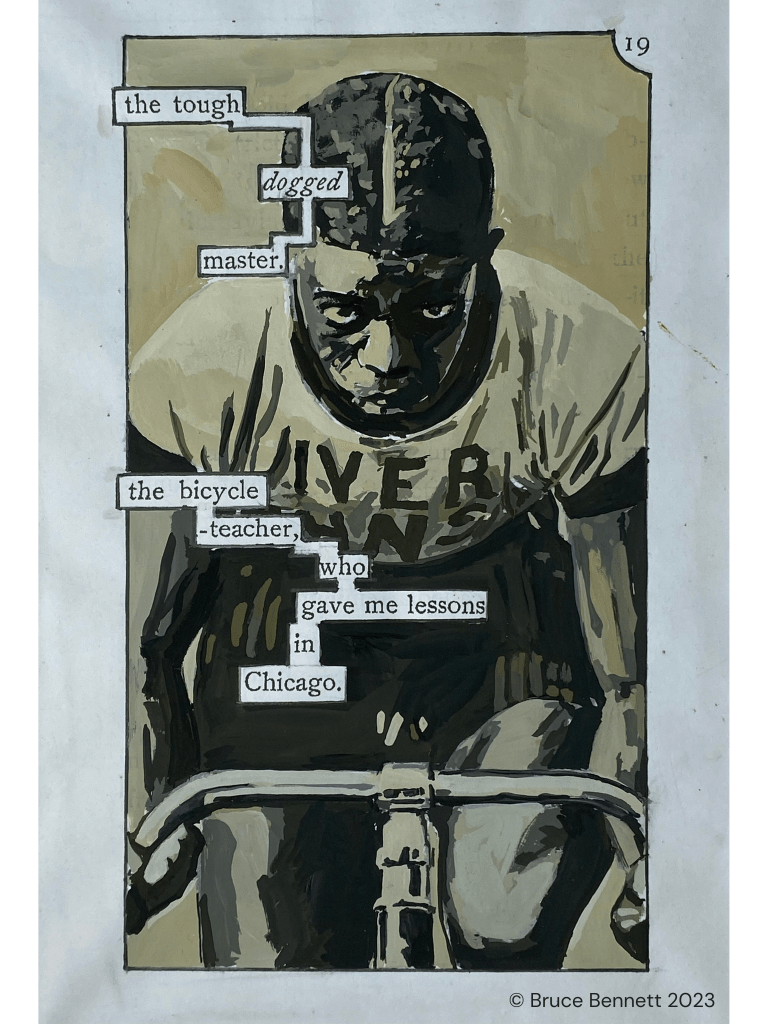

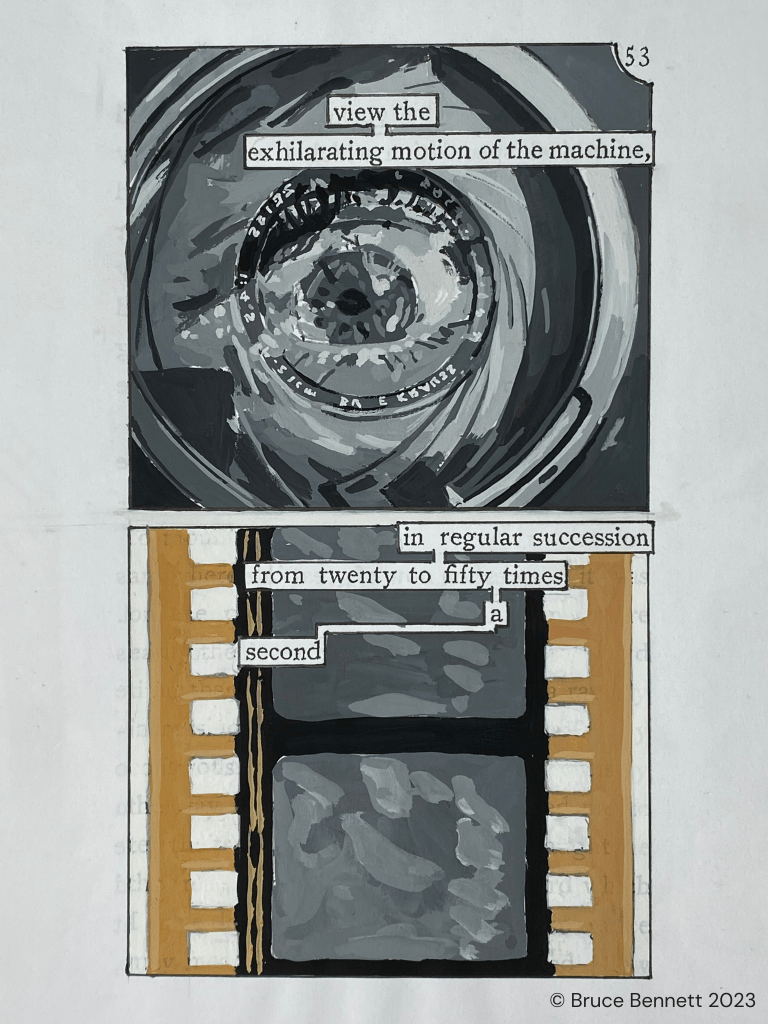

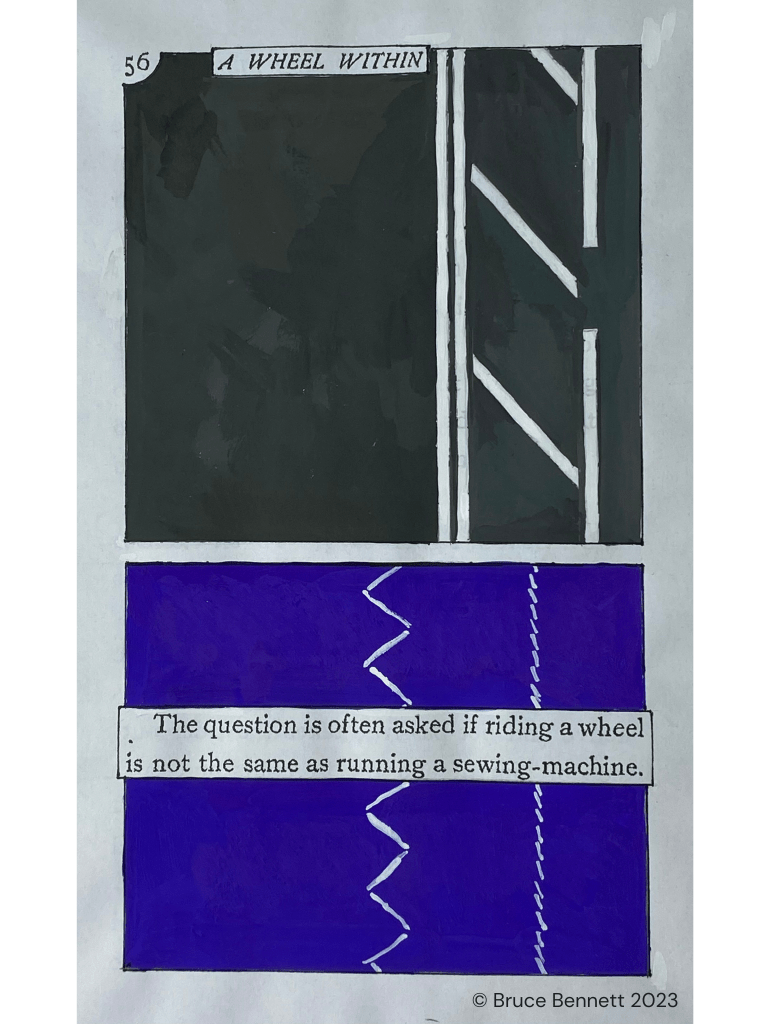

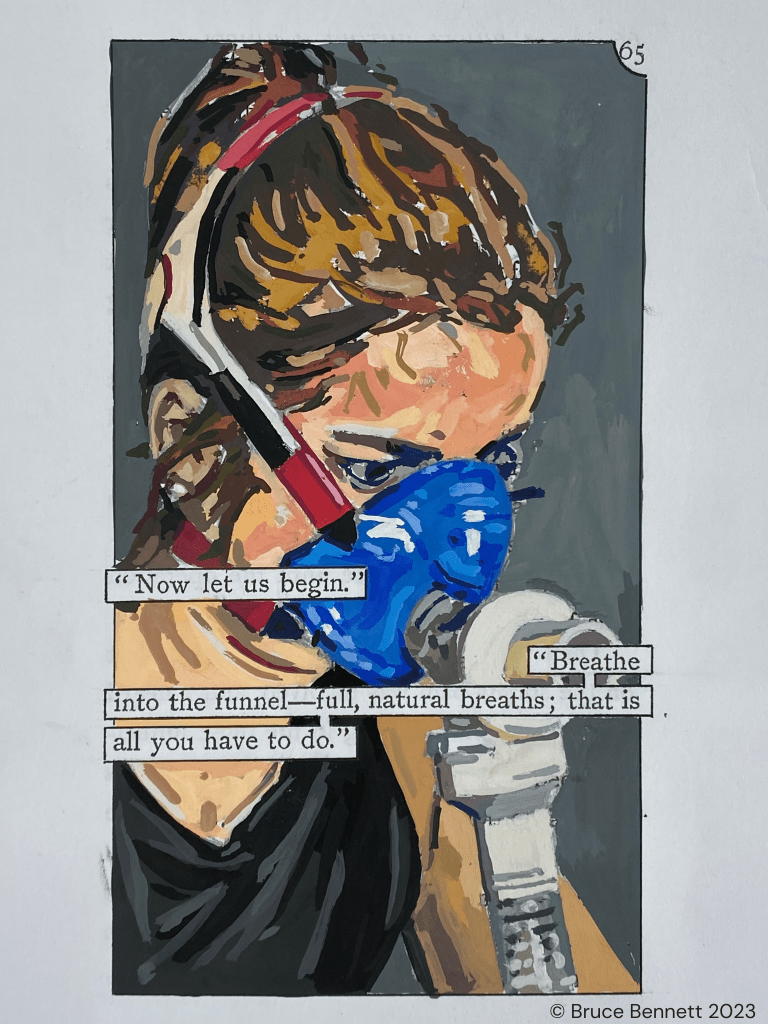

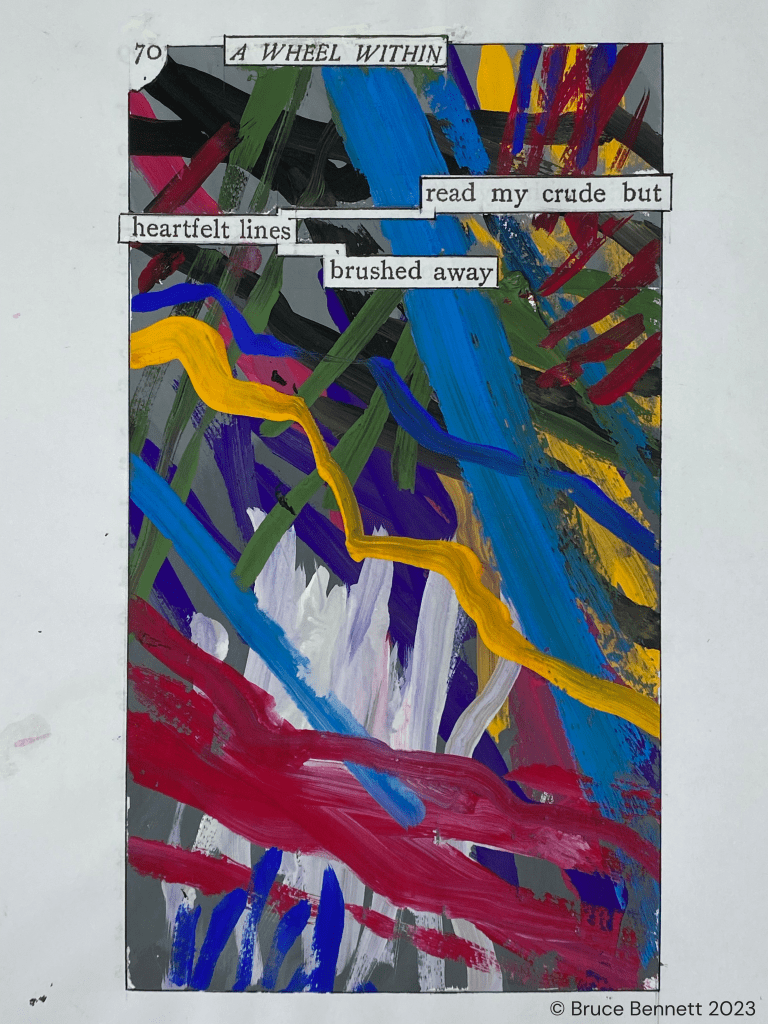

The book’s publication also marked a key historical period for my project, since the 1895 peak of the bicycle boom in Europe and the US, coincided with the birth of cinema, marked most famously by the first public screenings of films by the Lumiere brothers in Paris on December 28th of that year. Willard’s book is a product of that revolutionary moment. I discuss A Wheel Within a Wheel in Cycling and Cinema over a few pages, but I found myself returning repeatedly to the ideas outlined so succinctly by Willard, and so decided to produce my own version of Phillips’ work, a cycling humument: A Wheel Within. In reworking the book, the images that I’ve drawn and painted over the pages of Willard’s essay are drawn from the research I did into the history of cycling culture and its relationship with cinema. Sometimes they’re used to illustrate the text directly, and at other times have a more oblique connection to Willard’s words. Among the visual sources are images from films, cycling magazines, adverts, art-works and cartoons as well as my own photographs and drawings.

While in some respects it might seem like an act of violence to erase and appropriate another writer’s work, one of the intentions behind this project is to celebrate the richness and poetry of Willard’s book and underscore the enduring relevance of this work on the bicycle, described by Willard in the conclusion as ‘the most remarkable, ingenious, and inspiring motor ever yet devised upon this planet’.